The Complexity of the Caste System

- Home

- Blog

- Caste system Series

- The Complexity of the Caste System

The Complexity of the Caste System

When I was still in my teenage years, I was ignorant to a point that I had only learned about the so-called caste system like many of my German classmates did. At school. In English class, when talking about the British Raj and Modern Day India for the next exam. And of course, we have also learned how the system and the discrimination based of it was banned by the new independent Indian Constitution. Thus, officially the caste system has not been existing ever since. To me, the young and naive girl I was, it had never crossed my mind that the thing I had just learned at school would have anything to do with me.

„A Tamil girl living in the diaspora.“

First Encounter(s) with Casteism

Imagine the following scenario:

You are outside in a shop, at the station waiting for your tram, in the bus during a long-distance ride, sitting on the table at a function or anywhere else minding your business and you meet another Tamil, (more than likely, an elderly man or woman). You get somehow into a friendly conversation and suddenly this question comes up:

“Appe, neenge endhe idam” [ So, where are you from?]

And if you failed to understand the real question behind it, you have probably answered by naming the city where you are currently living – like I used to do so. But then immediately the second – more precise question would pop up:

“Ille, ungadhe Amma Appa oorule endhe idam” [No, I mean where are your parents from back home?]

Little did I know that my parents birth place would reveal anything about the amount of respect and attention this particular person would grant me for the rest of the conversation, provided this person will continue talking to me and not awkwardly end it by becoming less talkative or even silent. It took me a few years to fully comprehend the meaning of situations like this. After a while I started to hear stories about broken families and relationships from my surrounding and the common cause? Yep, you guessed it right. Caste.

After this I slowly came to realization …

… that this system has been all around me without my knowledge and shaping my life directly or indirectly. However, up to this point it happened rather unconsciously because my parents never talked about this openly with me. And this – is in fact- problematic. I think it is safe to say that it was like a (cultural) shock. Moreover, I started to notice this all around me and I started to wonder. I wondered why most of the people in our surrounding or the ones we become acquainted with are often of the same caste. I remember asking myself as a young child why certain people never even touch a glass of water when they visit another household.

The relationship between Caste and Colour

Recently, I have been seeing on social networks like Instagram a lot of pages which call upon embracing our roots. Embracing our culture and decolonizing our minds. Unfortunately, I also came across posts about how racism, colourism and casteism were supposedly created by the white European colonizers and that we must get rid of this toxic self-hate. Don’t get me wrong I am all for embracing ourselves and raising our voices against any form of injustice, but we should not be so ignorant of ourselves in doing so.

„Yes, colonizers did in fact, took advantage of these hierarchical structures and perpetuated it to further turn us against each other but they did not create it.“

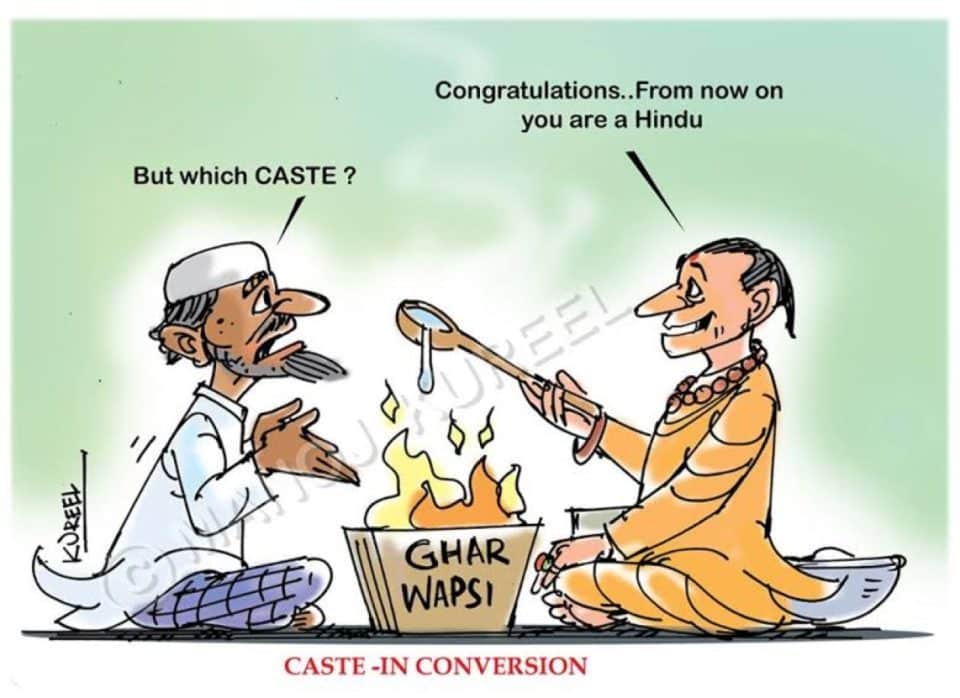

Let’s be clear about that. Casteism, also correlated with colourism, are mentioned as early as in ancient scripts like (dharmashastra) Manusmrti, Ramayana and Mahabharata. In ManuSmriti for instance you will find one of the earliest records of the caste system. The Hindus are divided into four varnas – the main categories:

“For the welfare of humanity the supreme creator Brahma, gave birth to the Brahmins from his mouth, the Kshatriyas from his shoulders, the Vaishyas from his thighs and Shudras from his feet. (Manu’s code I-31)”

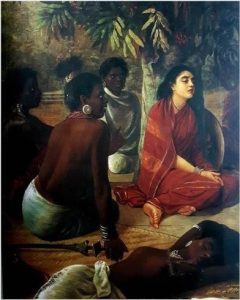

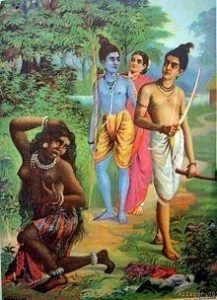

Besides naming based on occupation and ranking, also the privileges and penalties are predetermined. Interestingly enough, the term varna does not only refer to order but also colour. In Ramayana through the juxtaposition of Rama, a deity and avatar of Vishnu, and Ravana, a demon-king of Lanka/ Ilangai and a devotee of Shiva, you will quickly notice connection between caste and colour.

Sita in the Ashoka’s Garden at Ravana’s – Place surrounded by fearsome female demons

Sister of Ravana- Surpanakha

Redefining Culture

Hinduism is strongly embedded in our culture. And it is each to its own to believe, but what needs to be done is, acknowledging these sides of the story as well, even if it is not always openly discussed about. Just like the fact that people of lower caste were not allowed to enter the same temple as upper caste people. So, a few communities even build temples by themselves so they can practise their religion in peace. Even if casteism has been up to some point a crucial part of our culture, we do not have to continue to make the same mistakes – especially after becoming aware of its history. *

In my point of view, Culture is made by people. It is accumulation of external factors that define us to some extent.

„We should find means of expression within its space but should not feel suppressed or limited by it.“

Culture is dynamic and constantly changing. In the course of time we have rejected certain ideas especially concerning women and her role, i.e that girls don’t need education, child marriages etc. So why do we find it that hard to let go of casteism?

The Role of the Film Industry

I’ll tell you why. Because we keep falling back into daily practices of casteism without thinking. One culprit we should mention is cinema: Kollywood/ Bollywood. Cinema is mainly seen as a source of entertainment and therefore we often consume it mindlessly without being aware of its influences. Ever wondered about the ones behind the film industry? What are the most told stories in cinema? How are low caste people and their culture often portrayed in cinema? Why do they often only play a minor role in movies? – Although recently this is also being challenged by freethinkers and movies like Pariyerum Perumal.

If you also beginning to wonder and want to know more about it, I can recommend a short documentary on Youtube called The Invisible Other: Caste in Cinema (link will be provided at the end of this article). As casteism is a very complex topic, it is almost impossible to dwell upon every aspect of it in detail in this given frame. (Maybe this by itself could make a future article?)

How We Practise Casteism

We cannot always have a direct impact in everything around us. But what about the way we talk? Using words describing low castes as an insult. It’s the same as using the female genital as a cussword. I never understood that neither. To take pride in where you come from, by this I am talking to those who consider themselves from xyz -theevu (Island), who do not seem to understand how locality is linked to caste. The last time I was in Ilangai I witnessed people lying about where they actually come from, in fear of ill treatment or avoid contempt.

Now coming to very common response that is often directed towards someone who dares to talk against the caste system:

“You must belong to the lower caste. Only Dalits are against the system!”

Certainly, this is meant to hit a nerve at the same time, because those are the ones who are oppressed the most. It is important to know that within varnas, the four main categories mentioned earlier, there are over hundreds of castes /jaathi. Also, caste system in Ilangai is slightly different from the one in India. Even among Dalits, a general term used to refer to all low castes, there is discrimination. Basically, everyone is somehow superior to someone else (graded inequality– a term coined by Dr. Ambedkar).

„This idea prevents most of us to say anything against this system, because we like to maintain our privileges.“

Question Your Priveleges!

People will rather think about how there is always someone to feel superior towards instead of realising that everyone else is also inferior to someone else. And should this not be reason enough to come together and fight against this system? Therefore, even if one would strike back with the assumption that only one from the upper caste would be in favour of casteism, because they benefit from it, is not quite correct.

„So, it ultimately boils down to, whoever is able to recognize the injustice and is willing to give up his privileges is/can be against casteism. Similar to how men can also be feminist, you don’t have to necessarily be the one oppressed to be against it. Just because you personally haven’t been afflicted by casteism, does not mean nobody else could have been. It is also about solidarity.“

Pointing Fingers on Others

The next point is probably the most used when questioning any kind of discrimination be it racism, sexism or casteism.

“Then why do they behave like that”, “Then they should prove they can do better”.

This comment is degrading in so many ways. Firstly, it is highly stigmatizing. You are not even giving the person a chance to be anything other than what you expect him/her to be. Nobody is putting themselves in boxes just like that, unless a certain behaviour is expected by others. Even if someone turns out to be different than the “norm”, we often say things like “You are rather…for a xyz” – not a compliment. Period.

„Moreover, how can we expect another to dismantle our prejudices that we have been carrying with us? Why does one have to prove that he or she is not like that and try to change our mindset?“

Lastly, a well-known saying often used to console someone if you do not really know what else to say: Time heals all wounds. But time doesn’t care about anything really, it just passes. Nothing came into existence by simply time passing. There is always work that needs to be done first. Thus, I would like to end this article with a quote that perfectly illustrates the importance of action:

“Someone is sitting in the shade today because someone has planted a tree long time ago.” — Warren Buffett

Additions

- *To learn about modern eelam tamil history (including casteism): Check out Sinthujan Varatharajah’s Instagram @varathas – Highlight: alternatives

- To learn more about caste in cinema: Watch this Documentary or this decent movie

This is PART II of our „caste system“ series. See here the other articles of this series.

- Hidden and unseen and yet relevant – The caste system (Vijitha Vijay – PART I)

- The caste system – human contempt legitimized (Sinthuja Sathees – PART III)

- From prejudices to broken families and more – the caste system (Nerocy C. – PART IV)

- The caste system – the devil in a relationship (Anonymous Guest Autor – PART V)

- Breaking Barriers – How to Stop Maintaining the Caste System (Larvaniya S. – PART VI)

- From Kingdoms to Colonization – the Manifold Influences on Today’s Caste System (Shabin Shanmugalingam – PART VII)

- The Caste – Illusion of the Past or Mute Companion of the Future? (Sanu Sri – PART VIII)

Picture („Rajasthan … India“) under Creative Commons License from Nick Kenrick

This article was created as an enriching guest post for this blog. Do you also have one or more stories that you want to share with the readers and make them think? Then click here: Become a guest author and learn in which simple steps you can make a contribution to this blog.